Why do some carp get caught regularly and others go uncaught for years?

Simon Blanford takes a closer look at some recent studies to help give us an explanation

There are a number of ways we use to describe the difference between one person and another. We might comment on the colour of their hair or eyes. On how tall, short, thin or fat they are. On how old they look. But these are shallow attributes. They don’t get at our fundamental nature. For a more profound portrayal of a person we would describe each other not by our physical appearance but by our character. We’d decide whether a person was shy or bold, timid or aggressive, voluble or reticent. Whether they like to go out to new places or stay at home. Whether they watch the same type of TV show or film or like to dip their toes into the cinéma verité as well as the shock and awe of Transformers 1, 2… 33. Such a way of characterising people has very ancient origins. The Greek philosopher Hippocrates (he of the oath) is credited with the idea that we can be described by the kind of temperament (or humour) we exhibit. We each have a unique combination of different characteristics and together they are add up to fundamental description not only of who we are and what we are like, but also how we may behave in any given situation in the future. We call it our personality.

So humans are special. But so are dogs. If you believe dog owners. Dog owners would likely say that their dogs also have unique personalities. Your neighbour with the Heinz 57, the mutt that craps all over your lawn and barks maniacally at every visitor venturing up the garden path, will give you a detailed description of the mongrels character. Perhaps we humans are not that special after all. If all dogs (and in fact most pet owners would claim that their horse, cat, parrot, gerbil, is easily distinguished from any other horse, cat, parrot, gerbil on the basis of its personality alone) have their own unique personality. However, using dogs and other pets to demonstrate individual variation in behaviour is a little tricky. Concentrated selective breeding by us for the best labrador, poodle and cocker spaniel let alone for the ultimate labradoodle or cockapoo, can do strange things to the poor pooch’s mind. Inbreeding, not tolerated or seen in the wild, can make peculiar, neurotic behaviours (the very behaviours noticeable as a distinctive personality) the norm rather than the exception they are in natural environments.

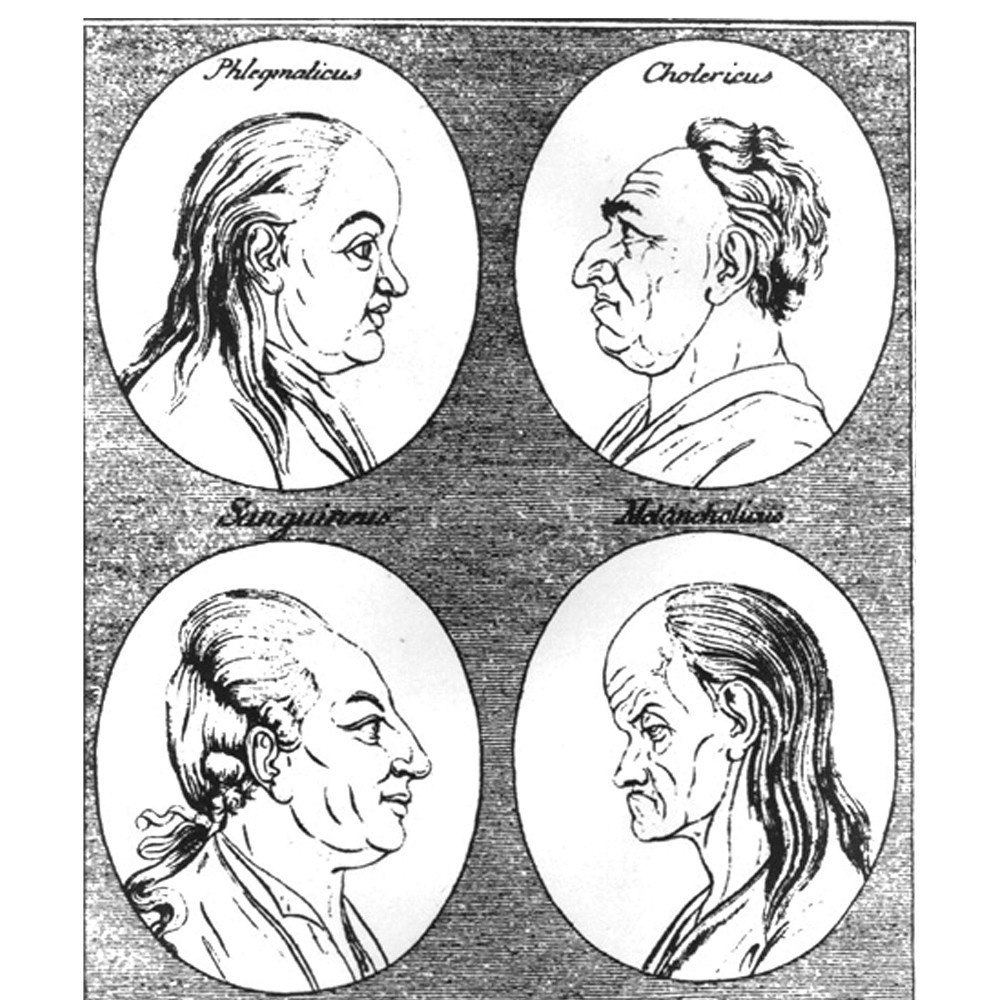

The four temperaments or humours. Clockwise from top right they are: Choleric, Melancholy, Sanguine and Phlegmatic. An ages old concept that lead to the character-isation of our five core personality types

The four temperaments or humours. Clockwise from top right they are: Choleric, Melancholy, Sanguine and Phlegmatic. An ages old concept that lead to the character-isation of our five core personality typesSo if the varied personalities of dogs and other pets can be explained by the fact that we have chosen what they should be like rather than how wild environments have selected them (if nature did it they’d all still be wolves) it follows that wild animals don’t have personalities. How can they. They are pretty much all the same. A rabbit is a rabbit. A pigeon is a pigeon. A bream is a bream. You don’t find one pike lounging on the couch stuffing itself with roach flavoured crisps while another swims laps around a watery track to better improve its attack speed. It’s PERSON-alities we’re talking about here after all.

Not so long ago biologists might have agreed with this view. Biologists were more interested in broad patterns of behaviour so they could get a handle on how populations and species should maximise their survival and leave lots of offspring. It would be poor research practice to look at one individual of a species and extrapolate what it does to cover all the other members of that species. You wouldn’t want, for example, to study The Burghfield Common and claim the fat fellow represents all carp. When odd behaviour by one animal was observed in experiments, biologists put it down to that individual being a bit strange and would soon be weeded out of the population by disease or predators. Or perhaps, it would revert back to more ‘normal’ behaviour if only it could be observed a bit longer. So researchers bent on explaining broad patterns generally ignored individual behaviour in favour of studying group and population behaviour – what animals generally do under any given situation.

That was then. But certainly not now. For the last twenty years or so there has been an explosion in research that deals with how animals differ in their individual behaviour and what that might mean more broadly. One of the first studies that prompted this shift was done on an American member of the perch family – the humble pumpkinseed sunfish. The researchers set out to trap some fish to take back to the laboratory to use for some behavioural experiments. In doing so they found that some fish entered the traps they had put down in the water and others stayed away. Not unusual perhaps. Maybe the ones that entered the traps were particularly hungry and were looking for food whereas the ones that stayed away were already well fed. Not so it turned out. When the fish were tested again the researchers found that those fish that originally entered the traps were much more likely to do so again and those that didn’t enter traps were much more likely to avoid them again whenever they were placed in the water. What’s more, in the lab it was found that trap-entering fish were quicker to explore a new environment, spent less time in shelters, moved in the open water of the tank rather than staying at the edge and accepted novel food items very quickly. The trap-avoiding fish pretty much did the opposite.

It seemed clear that in this population of pumpkinseed there were bold, adventurous, risk-taking fish. Conversely there were also shy, timid unadventurous fish. Both ‘personality’ types came from the same species, from the same population of that species, living in the same water and yet each individual’s behaviour was consistently different from other members of the population.

This is a humble member of the perch family: a pumpkinseed sunfish. It was one of the first species studied that revealed individuals varied in their personality

This is a humble member of the perch family: a pumpkinseed sunfish. It was one of the first species studied that revealed individuals varied in their personalityThese differences have shown up in a wide range of animals. Pretty much all the studies conducted so far – studies ranging from those on chimpanzees to hyenas, great tits to quail, trout to salmon to guppies to sticklebacks and even those on crickets, honey bees and water striders – have all shown wild animals too have something akin to “personalities”. Given this biologists now recognise five core personality traits for non-human animals: some individual animals are very shy, some bold; some are avid explorers others avoid new areas; some are very active, others are couch potatoes; some are aggressive others really not and some are very social and others asocial. Each individual animal is a combination of traits from across this broader range of characteristic behaviours. Underlying and driving these behaviours are the hidden reasons, the proximate mechanisms that create personality. Differences in metabolic rates, in organ size, in hormone balances and other chemical gubbins that act on the neural system to prompt animals, and of course us, to behave the way we do.

Rather unsurprisingly establishing that there will be a range of personality types in any population of animals means that what personality an animal like a carp has will fundamentally influence how they get through life. Just as our personality affects everything we do in our long lives. Some fish, for example, like the open water and will venture out into these dangerous spaces to seek food. Other fish, the shy, more timid ones prefer to keep in and around cover, the open water makes agoraphobes of them. At least for parts of the day. Shelter seeking fish do venture out from cover but may only do so at during particular times of the day when they feel safe. The night is an obvious time but so too may be very cloudy days when light levels are low, or when the water is turbid or even when it is raining and the surface made opaque.

Fish are one of the best-studied animal groups in terms of variations in behaviour. It doesn’t matter whether it’s a bass, a trout or a carp, individuals in these species have shown unique personalities

Fish are one of the best-studied animal groups in terms of variations in behaviour. It doesn’t matter whether it’s a bass, a trout or a carp, individuals in these species have shown unique personalitiesNatural food in the open water can be quite different to food sources found in and around cover and this leads fish to specialise in what they eat. After all, it takes a little while to learn how best to catch or collect certain food items. Different skills are needed to approach, grab and dispatch a well-armed crayfish compared to those needed to identify and fully exploit a bloodworm bed. As each fish gets more and more practised at finding and eating particular food sources they become more specialised in them. That doesn’t mean that they specialise on one or a few food types to the exclusion of others but it does mean they are more likely to forage deliberately for food items that they have become good at catching. Switching between food items will also happen more often for fish that are adventurous and who venture out to forage in open water more – no point in being a risk-taking fish unless you take risks. The less adventurous fish hanging around near that nest of snags or keeping close to a reedbed or under an extensive covering of lily pads will not only develop different feeding skills but may also specialise more.

A lean mirror that picked up a snowman presentation way out in a large lake. It wouldn’t have seen these baits before and was happy to brave the dangerous, wide-open spaces of the lake. A bold, adventurous personality?

A lean mirror that picked up a snowman presentation way out in a large lake. It wouldn’t have seen these baits before and was happy to brave the dangerous, wide-open spaces of the lake. A bold, adventurous personality?Over time the behaviour of the fish affects not only what the fish eat but also their shape. A study conducted on carp showed that stay-at-home, sedentary fish tend to become deeper in the body with relatively small fins. Why put any of the energy you get from food into large costly fins if you never use them to swim anywhere? Fish that inhabit more open spaces and travel a lot develop more streamlined bodies and large fins, the better to help them move through the water.

One other aspect is worth bringing up (though it’s not clear how it related to personality). Some fish seem to consistently seek out the company of others. But not just any old fish they happen to meet. They seek the company of a particular fish they already know. If the fish they like to hang out with is removed (say by mean biologists wandering what will happen) the fish left behind will hang around by itself, not making new acquaintances, until the original fish is returned. When it is, they go off together. Biologists don’t talk about fish making ‘friends’ of course but it is the case, for whatever reason, that bonds between individuals can form and last for long periods of time. If you’ve ever seen a pair of carp that always seem to hang out together this might be the reason.

Last month Gaz Fareham described Heather The Leather and The Dustbin as open water fish whereas Pearly and The Baby Orange were more likely to be found in the snags around The Gate spot

Last month Gaz Fareham described Heather The Leather and The Dustbin as open water fish whereas Pearly and The Baby Orange were more likely to be found in the snags around The Gate spotTo all that said, does the fact that fish really do have different personalities influence anything about the way we fish for them and how easy they might be to catch? Does it imply, as has long been suspected by carp anglers, that there really are ‘mug’ fish out there in our ponds, lakes and rivers? And of course it does. Active adventurous fish are often the way they are because they have high metabolic rates. A high metabolism causes the fish to burn through whatever it has eaten quickly and fuels the need to seek more food. Early work on largemouth bass (the darling of American fishermen) strongly showed variation in capture rates. Some individuals were never caught. Many were caught between two and five times. And then there were a few individuals who were caught fifteen or more times with one being caught more than twenty times. In another study, trout showed a similar pattern with some individuals being caught nearly twenty times in a short summer season and others never. More detailed work showed that the personality of the fish was responsible (bold fish got caught lots) and that this was linked to bold fish having high metabolic rates. Not only were they risk takers but they also had to feed more often.

A short tubby common extricated from heavy cover on a free-lined lobworm. Where it lived and its body shape might suggest a timid, sedentary fish that rarely ventures out into the open water

A short tubby common extricated from heavy cover on a free-lined lobworm. Where it lived and its body shape might suggest a timid, sedentary fish that rarely ventures out into the open waterOf course speculation as to why some fish very rarely come to the bank and some get labelled ‘mugs’ because they get caught regularly has fuelled many articles and considerable speculation in the carp fishing world. Just last month in CARPology, Gaz Fareham, writing of his experiences fishing The Car Park Lake on the Yateley complex described Heather The Leather and The Dustbin as open water fish whereas Pearly and The Baby Orange were more likely to be found in the snags around The Gate spot. The description of their habits neatly falls in with them being either adventurous open water explorers or unadventurous individuals that like to stick to cover and spend a lot of time in one small area. That they get caught suggests they are not the shyest fish. Some of the shyest, most intransigent fish were listed by CARPology in an article on their website back in April this year (the article was called ‘14 Fish We Thought Were Dead’ if you want to have a look). Some of these fish, like Hilton’s ‘Linear’, Ringland’s ‘Jumbo’ or ‘The Missing Mirror’ from Horton Church Lake, might be very timid, have low food requirements because of their sub-zero metabolic rates and compound the difficulty in catching them by restricting their diet.

Timidity, a lack of exploratory behaviour coupled with a low metabolic rate (which many timid personality fish have) starts to make catching these individuals more and more difficult. Add the fact that they might also be dietary conservatives and you have the combination of traits that make for something legendary. Dietary conservatives, as I wrote about last month, are those animals that are very unadventurous in the food they include in their diets. New food is avoided and often for long periods of time. Whether risk-taking explorers can be dietary conservatives isn’t clear but would seem to be unlikely as by their nature these fish are more likely to be adventurous consumers, those that rapidly test and include new food items into their diet. Tests to see whether generally shy fish could be caught more regularly showed that, rather unsurprisingly, presenting bait close to where they liked to hide away produced more of their personality type than fishing the open water. Simply identifying the drowned trees, the weedbeds, sunken cars and the like and then fishing tight to them may well produce one of those carp that rarely visit the bank.

Researchers have also suggested a further twist. Shy fish that are also have a very narrow diet, that is those fish that might be dietary conservatives, might be more likely to fall to a natural bait rather than an artificial one. So if you’ve identified a key feature, one that you might expect may hold that elusive, tight-lipped carp, and it hasn’t fallen to the usual boilie, pellet or particle approach, try switching to worms.

One question does remain to be answered. While the above has been told from the point of view of individual animals we could take a step back and ask if different breeds or strains of the same animal behave differently. For example, are pit bull terriers generally more aggressive than poodles? Or bringing the context back to carp, we might address that perennial question: are common carp very different to mirror carp? Are they more difficult to catch?

The simple answer is that yes, on the whole, commons are more difficult to catch than mirrors. How do we know this? Well, if you recall two months ago in this series Part 3 addressed whether carp were intelligent. Carp are fast learners, they have very good memories and as could be seen from the video posted to CARPology’s website to accompany the article (search on the website for ‘The Carp Part 3: The Clever Fish?’) they dramatically alter their behaviour around hookbaits once they have had experience of being caught. In describing the carp’s capacity to learn and remember I was treating all carp as the same but in doing so I was, how shall I put it, being somewhat economical with the real reason the studies from which the information came were conducted in the first place. These studies were interested in carp learning and remembering but they were also interested in finding out whether wild strains – that is common carp – were quicker to learn and remember than more domesticated strains (mirror carp) and whether they behaved differently around a baited area.

Mirror carp were not only easier to catch but were also slower learners, investigated and accepted artificial food more readily and were much more likely to have bold, adventurous personalities. Why this should be the case is bound up in the rearing backgrounds of the two fish. Carp were the first fish to be domesticated and the process has dramatically altered, not only the look and shape of modern carp but also their behaviour and cognitive ability. The impact of domestication on the behaviour of our carp is what I’ll be talking about next month.